- Home

- Bram Presser

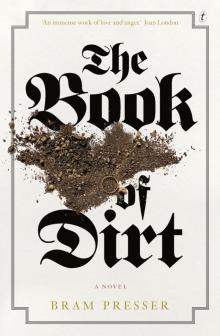

The Book of Dirt Page 11

The Book of Dirt Read online

Page 11

‘Filter?’

‘No need, thanks.’ She leaned forward as Františka struck a match. A plume of smoke rolled up her face. ‘It’s nice, this,’ she continued with a meaningless gesture around the room. ‘We have some freedom now. I used to worry. I didn’t want you to feel—’

‘Pshah.’ Františka waved away the smoke. ‘You know how it is. This too shall pass.’

‘Jiří is pleased for me…for us. He says the company has reddened my cheeks. Meanwhile he grows pale in the shadows. I swear the man is a chameleon. Not that he talks about it. I know only that he has associates. Nothing more. I’ve half a mind to sniff at his collars, but if there’s a mistress it’s she who is being cheated. I can’t see my dresser for his gifts. Search out every opportunity, he says. There is money to be made in the occupation.’

‘And the boy?’

‘He listens to his father. Then, the moment Jiří leaves in the morning, he, too, is out the door. I worry about him but what can a mother do? He is of that age.’

‘Maybe he is right. Ludya too. Personally, I dread these new opportunities. Here we are, more secure than ever. The girls, happy, fat. But we are feasting in the eye of the storm. One way or another it will come undone.’

‘You fret too much.’ Ottla smiled. ‘It’s like you no longer trust comfort. But look at you. How long has it been since you’ve come to my door? When did I last see you duck beneath the window ledge as I passed by? Now we go to cafés, the cinema, sit by the river. You fill your ration cards with money honestly earned. Face it, Frantishku, this occupation suits us. Now gather your things. The children will be home soon and we have a date with Lída Baarová. I didn’t much care for her in that last movie…what was it? Virginity. Yes. But this new one, a romance, they say…I might have to reconsider.’

‘She’s awful.’

‘It’s our national duty.’

‘To wallow in the muck of bad taste?’

‘Oh Frantishku, you don’t know? Lída Baarová…She’s taken Goebbels for her lover.’

4

Each night, as its inhabitants slept fitfully behind windows blackened to hide them from enemy pilots, the city transformed into a new and ever more frightening beast. Hideous plates of armour settled on the walls of its grandest structures, weighing down gargoyles and statues, and trapping the air so that the stench of half-digested hope hung on the dawn.

Behind a grey door on the second floor of an apartment building in Biskupská Street, Jakub R rose with the jangling of the alarm clock. In the darkness he felt the comforting presence of his mother, who still saw in him the future of their rabbinic dynasty, and the aura of an absent, yet omniscient father.

Jakub pushed the sheet aside and unfolded the nightgown that had protected his head from the wooden floor. It was still an hour before he would need to leave for work. He now had a rigorous, if not lucrative, routine—four days at the school in Jáchymova Street and two in the community archives—so Jakub R continued his dreams in the cramped kitchenette, stirring his coffee and telling himself that perhaps, when he stepped outside, he would find that the world had not changed for the worse.

A cough from the next room.

One never escapes, he thought. There is always a trail. The hopeless, the weary, the heartbroken: eventually they will follow. And they did: Gusta, Růženka, Hermann and little Shmuel. Until the occupation, their presence had mostly gone unnoticed. He had taught them to get by in the city. But after four years of familial responsibility in the tightening vice that was his city, Jakub found himself trying to stave off resentment. His landlord had recently increased the rent—‘On account,’ according to the letter, ‘of the additional tenants and the decrease in security of a Jew seeing out a long-term lease.’

It was his penance, he knew, for having deserted his sick father, for not having come sooner to help his family. Now, for his recalcitrance, his mother lay in his bed in Biskupská Street with Růženka, while Hermann and Shmuel slept on the couches. The village folk had been good to his family, it was true. When they finally came to accept that their rabbi was not long for this world, they had made a collection of coins for his care in the city. Even some of those from across the bridge contributed. But word of pogroms in not-too-distant lands had tightened their purse strings and so, despite the best intentions of a community who owed the good tidings of their souls to this man, Rav Aharon and his family departed with little more than their carriage fare and the warm wishes of a terrified people. It was a mercy that the village folk never learned that their beloved rabbi died in a bleak hospice, writhing in agony as his helpless wife wailed beside him.

Jakub R tried his best to shield his family from the snide remarks of his neighbours. It was clear that they had come to begrudge the extra bodies. Tempers flared, most often outside the water closet that all the inhabitants of the second floor were forced to share. ‘What is this,’ said the widow Žuženka, ‘some kind of ghetto?’ Most aggrieved were the younger Jewish tenants. ‘Yesterday I was late again,’ said Albert Weil, the paper trader. ‘They gave me my second warning, you know. These people need not look for excuses to fire a Jew. Now my future is hanging on your mother’s bowels!’ Jakub explained to Gusta and his siblings that things had changed, that they might have to wait until after eight before venturing into the corridor. Gusta just shook her head, unable to comprehend city life.

On the day of the first student demonstration, Jakub R returned home late, national colours pinned to his lapel and Masaryk cap in hand, only to find his little brother curled up against their mother in tears. ‘I want to go home, Jakub,’ Shmuel said between sobs. Jakub patted the boy on the head and turned to Gusta. ‘Is Heju here?’ he asked, but did not wait for an answer. He already knew. Hermann would still be out among the students. He fancied himself one of them. Soon I will go to medical school, he once announced with certainty. But there was no money to send him to Charles University. So, instead, each day he followed Jakub through the winding streets of Nové Město to the National Square, before heading off south towards Kateřinská to loiter outside the medical faculty. Hermann made friends easily. The students let him into their clubs, their dormitories, their homes. He would often disappear late into the night, well past curfew, while Gusta sat quivering by the door until he stumbled home, invariably drunk on the potent brew concocted in the university’s chemistry laboratories.

The door swung open and they all turned around, expecting Hermann. It was Růženka. Like most nights after curfew she had been downstairs, in the Zahradníks’ apartment, her ear against their radio. ‘That box is cursed,’ Gusta said when she first arrived in Prague and heard the disembodied voices crackle from the strange contraption on Jakub’s dresser. ‘How can one trust words when the speaker hides his face?’ she asked. ‘It is all lashon hara, malicious gossip. For that box we will have to repent.’ Her relief was palpable when the decree came for all Jews to hand in their radios. ‘Now you will see,’ said Růženka. ‘From this day it will only be gossip.’ She did not speak to her mother for a week, as if it had been Gusta’s fault. She refused to join the family for dinner, instead knocking on the doors of their non-Jewish neighbours, asking if she might listen to the nightly broadcasts. Every one of them declined, some politely, others less so, until Kryštof Zahradník stopped her in the washroom one day and whispered that she should come to his apartment after sunset. Kryštof and Karolina didn’t seem to care that they were helping a Jew break the prohibition; they were listening to Jan Masaryk’s dispatches from England, which itself was punishable by death.

‘There was shooting,’ said Růženka, more a statement than a question.

Jakub nodded. ‘Yes, after the march. We cleared the streets, the SS held their weekly peacock parade through Wenceslas Square, and then the crowd reconvened. I kept my distance and lost sight of Heju early. He headed to the square with his friends. Then the soldiers arrived.’

‘They are saying a man is dead. A baker. And fifteen others

in hospital, mostly students. Some National Festival.’

‘He opened the window and watched as they ran past,’ said Gusta softly, tilting her head towards Shmuel. ‘They came in bursts, with fury in their eyes. They were screaming. He was screaming. It was like the plague of the firstborn. Only divine intervention stopped them from coming through the door and dragging us from this place.’ The boy was now dozing against her arm. ‘Tomorrow I may still mourn a son.’

‘Mother,’ said Růženka. ‘They were nowhere near here!’

‘They were. Or their evil spirits. They came from the gates, behind the church, to take us all away.’

At dawn, a dishevelled Hermann tried to sneak through the door, but his mother and siblings surrounded him. He barely had the strength to recount the story of his arrest and immediate release by the Czech police, and the promise he had made to the officers that he would stay off the streets until the situation had calmed and the Reichsprotektor ceased baying for student blood. ‘It was past curfew,’ he said as he lay down on the couch. ‘The streets were filled with German police detachments. We hid out near the hospital. Some of our friends were hit.’ Hermann pulled the sheet over his head and was asleep before his mother’s next question.

Gusta R experienced the occupation from the window in the bedroom of Jakub’s apartment. She was frightened among the masses. Whenever Jakub tried to convince her to go outside, insisting that the city could yet be her home, her eyes narrowed and she said, ‘This is exile. At home I knew everyone’s name.’

A month into the occupation, Jakub could see that even the corridors of the apartment building had become foreign to her. She stopped speaking to the neighbours. It was a mournful quarantine, but she had taken to it with determination; she wore only black, sat on the lowest chair, took off her jewellery, and kept her head covered with a threadbare shawl. From time to time, Jakub would come home and catch his mother in conversation with the one picture that remained of her husband. She still counted on him to protect her, and would sleep with the picture under her pillow so that his spirit might watch over her dreams.

In the fortnight following the student demonstration, Gusta Randova began to wonder if her mind was playing tricks on her. Black water seemed to trickle under doors and windowsills, and, in the puddles that crept towards the cracked walls of the apartment, she thought swarms of cicadas were breeding, clinging to the wooden beams behind the plaster, and rubbing their wings in chorus, until they sounded the news that Hermann and his friends had waited for in shrill alarm.

The student, Jan Opletal, is dead.

Gusta pressed her hands against her ears. Růženka crackled like the radio with words that were not her own. Hermann raged with the voice of a thousand students. There would be another demonstration, this time bigger, a wake like Prague had never seen, a wake worthy of a martyr. Only Jakub spoke softly, but it was his voice that cut the deepest. ‘You mustn’t go,’ he said to Hermann. ‘They will be looking for an excuse. It is suicide.’

For two days Hermann stayed in the apartment and kept to himself. On the third, he grabbed his coat and cap and rushed out the door.

The city raged in defiance and then fell quiet. Jakub set off for work and immediately sensed the presence of a malevolent seraph stalking the streets of Prague. The night had stolen the drunken, rebellious cries of the previous day and carried them, without trial, to a secret slaughter. But their spirits would not stay silent: the wind moaned with the ghostly echoes of young voices. The seraph continued its rampage into the new day, feasting on fear and anger, breaking open doors, chasing its prey from windows and grabbing those who hid in corners.

Jakub looked over his shoulder, checking for the beast, ensuring that it was not heading back towards Biskupská Street in search of Hermann. The boy was courting trouble; he had fought with the police outside the law faculty, and had driven them back over the bridge. Jakub could only hope that the mezuzah on their door might offer some protection.

At last Jakub reached the square, and his old spirit guide Jan Hus. The great martyr covered his eyes with a giant, bronze hand while the Hussite minions tended to a cemetery of rotting garlands below. The national colours had melted into each other, and ran like bloody tears through the gaps in the stones. A blast of warm wind tore across the square from the south and Jakub knew the seraph was near. Taking his leave from the monument in five backwards steps, as he was still conditioned to do, Jakub turned and rushed up Pařížská Street, hoping to hear the sounds of children at play. But there was only one other person in Jáchymova when he arrived: Georg Glanzberg sitting on the kerb, waiting.

‘School’s out,’ said Georg. ‘The whole city is in lockdown. Father sent me here; he knew you’d come. We need to get off the street. Now.’ Georg grabbed Jakub’s cuff and led him the two blocks to the family’s home on U Starého Hřbitova. ‘Von Neurath was summoned to Berlin with Secretary Frank as soon as Hitler heard. He won’t allow such weakness. In the past month he has survived three assassination attempts. And now this. He is celebrating his invincibility the only way he knows how, with an orgy of violence. The reprisals are already underway.’

‘This simmering calm,’ Professor Leopold Glanzberg said as he turned from the window. ‘It cannot be trusted.’ Jakub and Georg were standing near the radiator, still brushing the snow from their jackets. From the next room, the clattering of plates and a woman’s merry singing. Leopold walked towards the cabinet and reached for a bottle. ‘For your nerves,’ he said as he passed a tumbler to Jakub. Georg picked up his violin and tapped anxiously at its strings. Leopold poured one for him too.

‘A drink to luck,’ said Leopold, raising his glass. ‘L’chaim. A year ago and it could have been the two of you.’

Georg gulped down the whisky. It troubled him to see his father like this. The old man was quick to despair; he had retired from the bustle of academic life, found peace at the nearby Jewish Museum—dusting the plinths, straightening the exhibits. Professor Leopold Glanzberg came to rely on the daily ritual and, when not at the museum, would stand anxiously by the window, staring across the street at its ceremonial hall, pleading with his charges not to surrender themselves to the gathering dust. That his name had once echoed through the most hallowed academic halls of Bohemia, that he was once consulted by community leaders, rabbis and politicians alike was no longer of any consequence to him. He had given up the care of human souls for that of ones less finite.

‘The streets are almost deserted,’ said Georg. ‘Shopkeepers have not lifted their awnings. There is only the sloshing of buckets: German soldiers plastering the walls with posters. Another decree, of course. On my way back I saw an old classmate, who said the Germans have emptied the halls of residence and expelled anyone they suspect of involvement with the Opletal wake. Karl Frank wants to take Prague for himself—it is plain to see. The demonstrations made Von Neurath look weak so, while he was still trying to explain himself to Hitler, apparently Frank commandeered the official plane with a list of names in his hand. At this point my friend began to cry. If only it was expulsion, he said. Last night the student union meeting was stormed and the leaders taken away. As were some of the professors. Nobody has heard from them since.’

Leopold resumed his position against the window. ‘They’re dead, no doubt. And soon enough their loved ones will be receiving the bill for their executions. Boxes and bullets don’t come cheap. We pay in hard cash for this occupation.’

Georg stood up to pour himself another drink. ‘On Maiselova one of the posters says they’re closing the universities. It is not enough that they kill our students; they are murdering the institution itself.’ Georg raised his glass. ‘To the death of knowledge. And, of course, to you, Jakub. My friend. Quite possibly the last Jew to attain any. May they put you on a plinth across the street so that my father can dust your shoulders.’

They played chess late into the afternoon. Each game lasted as long as Georg decided it should, allowing him to test out new g

ambits before moving in for the kill. Jakub’s defences were clumsy, but occasionally Georg would sit back and look over the chequered battlefield, forced to reconsider his next move.

It was dusk when Leopold returned to the room. ‘The patrols are more frequent,’ he said. ‘Jakub should leave while it’s still light. His mother need not worry about two sons.’ Jakub considered his impossible footing on the board. Once again, every piece was in danger of falling to Georg’s perfectly positioned army. ‘Stalemate, then?’ he said as he got up.

Life had yet to return to the streets. Snow muffled the footsteps of the German patrols. Windows fell shut as Jakub raced the sun to Biskupská Street. There were still hours before curfew, but he did not trust the dark, the silence. The day had brought phantoms enough.

When he opened the apartment door and saw Hermann on the couch, Jakub stopped to kiss the mezuzah. The angel of death had passed over their home.

‘I should be on one of those buses,’ said his brother. ‘I should be with them.’ He had rushed to the dormitories when he’d heard, found them empty, saw the carnage. Books strewn across the floor, desks toppled onto their sides, broken glass and blood in the flowerbeds. Hermann began packing as soon as he got home. A few clothes, books, a spare pair of shoes. A blanket. He would need to travel light. There was no money for a train fare, let alone the migration tax. Anyway, Gusta would need it just to live. His only option was to walk, to stow away. He would make do wherever he landed. England. America. Palestine. He would join the army, the medical corps. One way or another he would be initiated on the front line.

Gusta cursed, then pleaded, then cursed again. Hermann sat by her side, explaining his reasons in his soothing voice, while she gazed at the picture on her lap, as if Rav Aharon might offer counsel. Their last hours together were spent planning Hermann’s journey, inventing adventures in foreign lands. Scheherazade in Biskupská Street. The sun arrived to take him, and they all stood at the door. Only Shmuel failed to appreciate the gravity of the moment; in his eyes his brother was a storybook hero.

The Book of Dirt

The Book of Dirt